How to Use Camera Shots to Improve Your Narrative Writing

Techniques for adding a cinematic experience to your stories.

Photo by Garvit Jagga on Unsplash

Stories have always been a cinematic experience.

Huddled around a fire, the ancients recited grand stories of heroes, and gods, and monsters. A tribal elder waved his arms majestically to show how Odysseus’ ship was tossed by the god Poseidon while the tribe’s younglings sat in amazement, imagining the tales of the Odyssey were playing out right in front of their eyes.

During the middle ages, stories were sung by traveling bards who recounted adventures of chivalrous knights, crusades, and maidens in distress. Songs of King Arthur and his knights echoed across the lands. Children and adults could sing to the melodies that regaled the tales of great battles.

In Elizabethan England, historical retellings and stories of revenge and murder played on large indoor stages for hundreds of people. Actors dressed as kings and queens and sets with crudely drawn depictions of the setting were brought on stage by stagehands. The audience imagined themselves standing in a castle in Denmark, not on the floor of an old theatre in London.

Today families sit on their sofas and surf through an exhausting amount of channels to find a piece of content that will hold their attention for more than 15 minutes.

A well-designed narrative draws the reader in, hooks them by the heart, and enlivens their curiosity. The ride you take them on as you zoom in and zoom out of locations and settings and characters’ thoughts and feelings is what makes readers invest their precious time with your words.

But how? How do we create a cinematic experience on the page?

Let’s take a lot at 4 different camera shots used in filmmaking and consider how each shot could be used to improve your narrative writing and create an experience your readers will never forget.

ESTABLISHING SHOT

Image via Citizen Kane.

Description

With an Establishing Shot, the writer stands back and provides a description of the narrative’s setting and environment. This is the widest angle possible of your story. Show the reader the haunted house in New Orleans, the battlefield in Kentucky, the beach in Santa Monica.

Using the Establishing Shot helps the reader understand the world the characters exist in while creating a sense of curiosity or possible foreshadowing of events to come. This is especially important in genre stories such as horror, fantasy, mystery, and history/historical fiction.

Characteristics

Establishes the setting.

Creates curiosity for the reader.

Creates tone and mood.

Can show the passing of time.

Example

The grey manor stands alone at the hilltop, mired in its own history of shame and violence. A wrought-iron fence surrounds it, keeping the ghosts of its past locked in like a prison. The wind howls through its broken shutters and the dense fog covers the grounds like a straight-jacket covering the soul of the insane. A faint light glows from a window at the very top. A gentle reminder to everyone below that the house still awakens from its gentle slumber.

MEDIUM SHOT

Image via Hunger Games

Description

The most common shot used in stories is the Medium Shot. The writer uses the Medium Shot to show two or more characters engaged in dialogue or physical interaction. The reader also gets an up-close look at a character — their body type, how they walk, what clothes they wear.

Because the Medium Shot gets the reader closer to the character's environment, the reader gets a feel for the characters’ movements as they interact with their surroundings.

Characteristics

Establishes and builds relationships between characters.

Introduces and describes a character’s physical features.

Offers the opportunity to show a character interacting with the environment.

Provides the reader with more details about the setting.

Example

“Are you sure this is the place?” Mark says to Amy as he looks up at the decrepit manor. Mark grabs a backpack from the trunk and gently closes it.

“Yes, I’m positive,” Amy says as she steps out of the passenger side, slipping on her windbreaker. Her face glows brightly in the thick fog.

Mark squints as he looks at the hilltop. “Is there a light on? I thought this place was abandoned years ago?”

Amy stares at the manor, remembering the tales of horror her grandfather told her as a child. “Let’s go find out who turned it on,” Amy responds as she walks past Mark.

CLOSE UP

Image via The Shining

Description

The emotion shot. This is the money shot, if you will. The writer brings the reader close to a character’s face to fully experience the character’s emotion. The reader sees the crooked, stained teeth of an old man, the perfectly structured jawbone of the young man, the squint of disdain in the teenage girl’s eyes.

The Close-Up is the perfect complement to the interior monologue most prose writers love to tell their stories from. Toggle between what a character is thinking and how those thoughts are shown on their face.

The writer uses the Close Up to build a relationship between the reader and the character. The audience connects with the characters through this shot. The reader is intimate with the feelings and reactions of the character during the scene.

Characteristics

Builds greater intimacy between a character and the reader.

Allows the reader to experience a character’s emotions in greater detail.

Gives importance to an object or detail within the setting.

Example

From inside the manor, excitement drips from the crazed man’s face as he peers from behind the curtains and looks out over the unkempt grounds. His eyes bulge and sweat rolls down his cheeks. A few strands of hair hang like nooses against his forehead. A large smile covers his face, revealing a full mouth of perfectly white teeth. His breathing hurries as he watches Mark and Amy walk up the long, labyrinthine walkway towards the manor.

EXTREME CLOSE UP

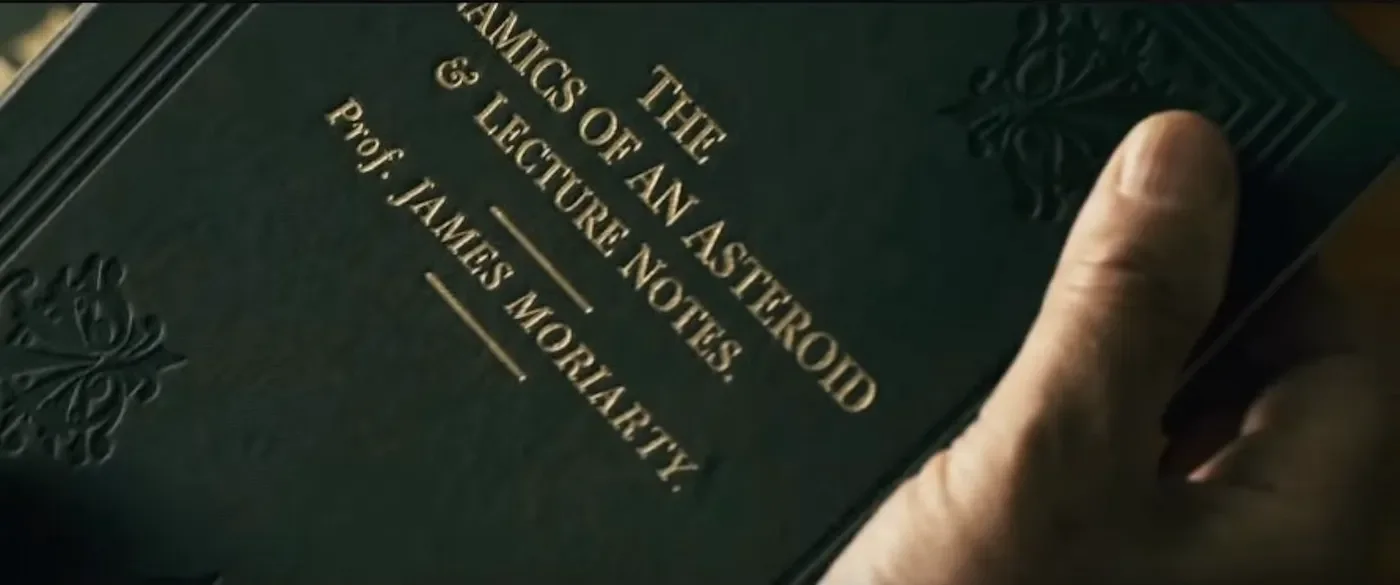

Image via Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows

Description

The writer zooms in tight to show a specific detail of an object or minute aspect of a character, something the reader must be shown explicitly because it normally hides in the narrative.

To draw the reader’s attention to a sensory response on a character — something non-verbal and subtle. Or it can be used to show the reader a specific detail of an objective that has importance in the scene and the overall story, such as evidence or clues to a case.

Characteristics

Emphasizes strong emotions or details of a character.

Directs the reader to only focus on what’s important on a character or object.

Create intensity and greater importance to an object.

Example

Amy clutches a small, green book in her left hand as she and Mark walk towards the manor. The edges of the book are bent and the pages are stained yellow from years of use. Embroidered in gold trim, the book’s title, Speaking to the Dead, sparkles in the dense fog. Amy’s grandfather gave it to her before his untimely death at this very house.

FINAL CUT

Let’s put the examples I wrote into a coherent sequence and see what we get:

The grey manor stands alone at the hilltop, mired in its own history of shame and violence. A wrought-iron fence surrounds it, keeping the ghosts of its past locked in like a prison. The wind howls through its broken shutters and the dense fog covers the grounds like a straight-jacket covering the soul of the insane. A faint light glows from a window at the very top. A gentle reminder to everyone below that the house still awakens from its gentle slumber.

“Are you sure this is the place?” Mark says to Amy as he looks up at the decrepit manor. Mark grabs a backpack from the trunk and gently closes it.

“Yes, I’m positive,” Amy says as she steps out of the passenger side. Her face glows brightly in the thick fog.

Mark squints as he looks at the hilltop. “Is there a light on? I thought this place was abandoned years ago?”

Amy stares at the manor, remembering the tales of horror her grandfather told her as a child. “Let’s go find out who turned it on,” Amy responds as she walks past Mark.

Amy clutches a small, green book in her left hand as she and Mark walk towards the manor. The edges of the book are bent and the pages are stained yellow from years of use. Embroidered in gold trim, the book’s title, Speaking to the Dead, sparkles in the dense fog. Amy’s grandfather gave it to her before his untimely death at this very house.

From inside the manor, excitement drips from the crazed man’s face as he peers from behind the curtains and looks out over the unkempt grounds. His eyes bulge and sweat rolls down his cheeks. A few strands of hair hang like nooses against his forehead. A large smile covers his face, revealing a full mouth of perfectly white teeth. His breathing hurries as he watches Mark and Amy walk up the long, labyrinthine walkway towards the manor.

I’d say that’s not too shabby. Sure, it still needs some fine-tuning, but the gist of the scene is there.

You can see how I take the reader on a journey from the establishing shot to establish the scene, to the medium shot to introduce the characters, to the extreme close-up to show a key detail, and finally to the close-up of the estranged man to create conflict.

FINAL CREDITS

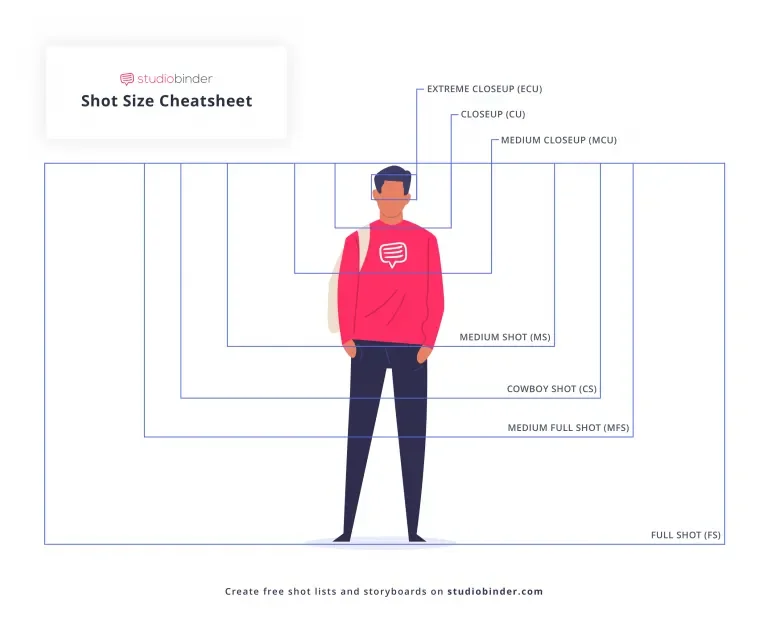

There are tons of different camera shots and angles in visual storytelling.

What I provided is just a glimpse of the opportunities and tools available to writers. Doing a quick search online for “camera shots” or “camera angles” will yield a whole bunch more than what I provided.

Image by Studiobinder

Using camera shots and different angles as a revision technique or as part of your outlining process can open up, literally, new perspectives and aspects of your story that you never thought of before.

And using camera shots doesn’t apply only to fiction. Creative non-fiction like personal essays, biographies, travel writing, food writing, and journalistic pieces can use camera shots to help create an experience for the reader.

Don’t just write a story; create an experience for your reader.

WRITER’S WORKSHOP

Now what? Here are a few ideas to get you started playing around with camera angles in your writing.

Read: Pick up your favorite short story, novel, or work of journalism and skim through several passages to identify the different types of camera angles the writer uses. Is there a particular camera angle the writer consistently uses? How does the writer use the various camera angles to develop character, build conflict, establish tone and mood?

You could also take a peek at a few flash fiction stories I wrote and see how I used camera angles.

Revise: Look at a work-in-progress or a story that you’ve published (on Medium!). Scan through your lines and identify which camera angles are used. Determine if there are other camera angles you could incorporate to highlight a key detail, enhance characterization, establish setting, develop tone and mood, etc.

Write: Throughout this article I’ve used several images to show what each camera angle looks like. Use the images to tell a story. Or, search the internet for other images to create a story.

FURTHER READING

If you enjoyed this article, then I invite you to take a look at a few others I’ve published on writing tips.

“A Fated Feast” is inspired by Prometheus Bound (1611–1618), a painting by Peter Paul Rubens and Frans Snyders, which captures the brutal torment of Prometheus as Zeus’ eagle relentlessly devours his regenerating flesh.

While the painting focuses on Prometheus’ suffering, this story shifts the perspective to the Eagle, transforming it from a mindless enforcer of divine will into a being capable of self-awareness, doubt, and existential horror.

Through this lens, “A Fated Feast” explores fate, free will, and the nature of oppression and explores the idea that Prometheus is not the only prisoner of the gods.